Best Practices

To ensure expected behavior when working with geometries, it’s recommended to follow these best practices:- Use language specific geometry libraries for creating, parsing and serializing geometries.

- Define polygon exterior rings with a counter-clockwise winding order.

- Define polygon holes (interior rings) with a clockwise winding order.

- Ensure longitude values are within

[-180, 180]and latitude values are within[-90, 90]. - For geometries crossing the antimeridian, cut them along the antimeridian into two parts: one for the eastern hemisphere and one for the western.

- Define geometries covering a pole in a specific way for correct handling.

- When downloading geometries from external sources (for example from STAC Catalogs), always verify these assumptions to prevent unexpected behavior before ingesting them into Tilebox.

Geometry vs Geography

Some systems distinguish betweenGeometry and Geography data types. The primary distinction lies in how edge interpolation is handled along the antimeridian. Geometry represents a shape in an arbitrary 2D Cartesian coordinate system and does not perform edge interpolation.

In contrast, Geography typically wraps around the antimeridian by performing edge interpolation, such as converting Cartesian coordinates to a 3D spherical coordinate system. Typically, Geography types limit x coordinates to [-180, 180] and y coordinates to [-90, 90], whereas Geometry types have no such limitations.

Tilebox does not differentiate between Geometry and Geography types. Instead, it offers a query option to specify a coordinate reference system. This controls whether geometry intersections and containment checks are performed in a 3D spherical coordinate system (which correctly handles antimeridian crossings) or a standard 2D Cartesian lat/lon coordinate system.

Terminology

Familiarize yourself with key geometry concepts. Point APoint is a specific location on the Earth’s surface, represented by a longitude and latitude coordinate.

Ring

A Ring is a collection of points that form a closed loop. The order of the points within the ring matter, since that defines the winding order of the ring, which is either clockwise or counter-clockwise.

Every ring should be explicitly closed, meaning that the first and last point should be the same.

Polygon

A Polygon is a collection of rings. The first ring, the exterior ring defines the polygon’s boundary. Any other rings are called interior rings, representing holes within the polygon.

MultiPolygon

A MultiPolygon is a collection of polygons.

Geometry libraries and common formats

Geometries can be expressed in different formats. The Tilebox Client SDKs delegate geometry handling to external, well-known libraries. Here is an example of how to define aPolygon geometry, covering the area of the state of Colorado using Tilebox Client SDKs.

GeoJSON

GeoJSON is a geospatial data interchange format based on JavaScript Object Notation (JSON).colorado.geojson

Well-Known Text (WKT)

Well-Known Text (WKT) is a text markup language for representing vector geometry objects.Well-Known Binary (WKB)

Well-Known Binary (WKB) is a binary representation of vector geometry objects, a binary equivalent to WKT. Given acolorado.wkb file containing a binary encoding of the Colorado polygon, it can be read as follows.

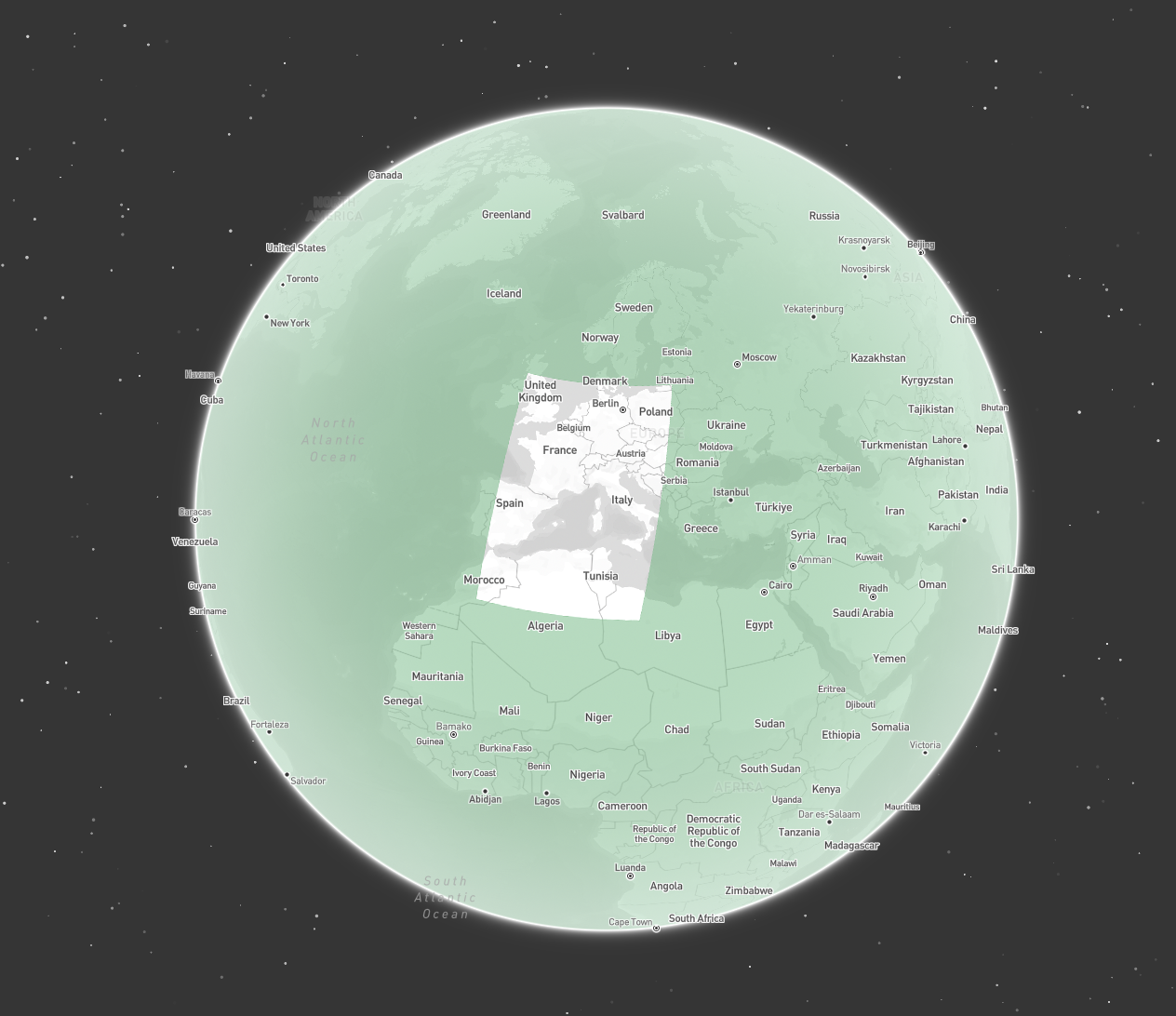

Winding Order

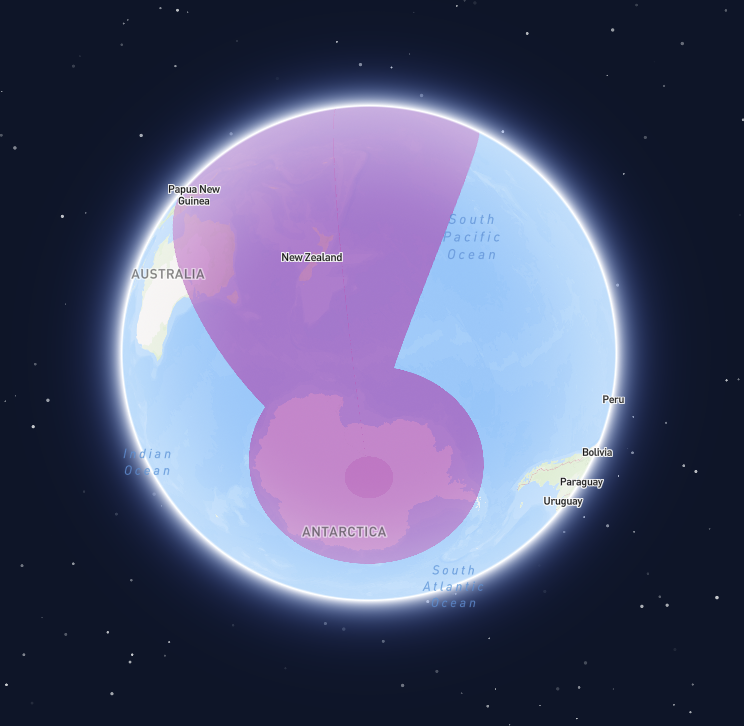

A ring’s winding order defines its orientation (clockwise or counter-clockwise), determined by the sequence of its points. Geometries in Tilebox follow the right hand rule defined by the GeoJSON specification:A linear ring MUST follow the right-hand rule with respect to the area it bounds, i.e., exterior rings are counterclockwise, and holes are clockwise.Thus, polygon exterior rings must have a counter-clockwise winding order, and interior rings must have a clockwise winding order. Failing to follow this rule can lead to unexpected query results, as shown below. Take the following

Polygon consisting of the same exterior ring but in different winding orders.

Counter-clockwise

Clockwise

Polygon with an exterior ring in clockwise winding order.

Instead, such geometries should be defined as a Polygon consisting of two rings:

- an exterior ring covering the whole globe in counter-clockwise winding order

- an interior ring specifying the hole in clockwise winding order

Polygon covering the whole globe with a hole over Europe

Antimeridian Crossings

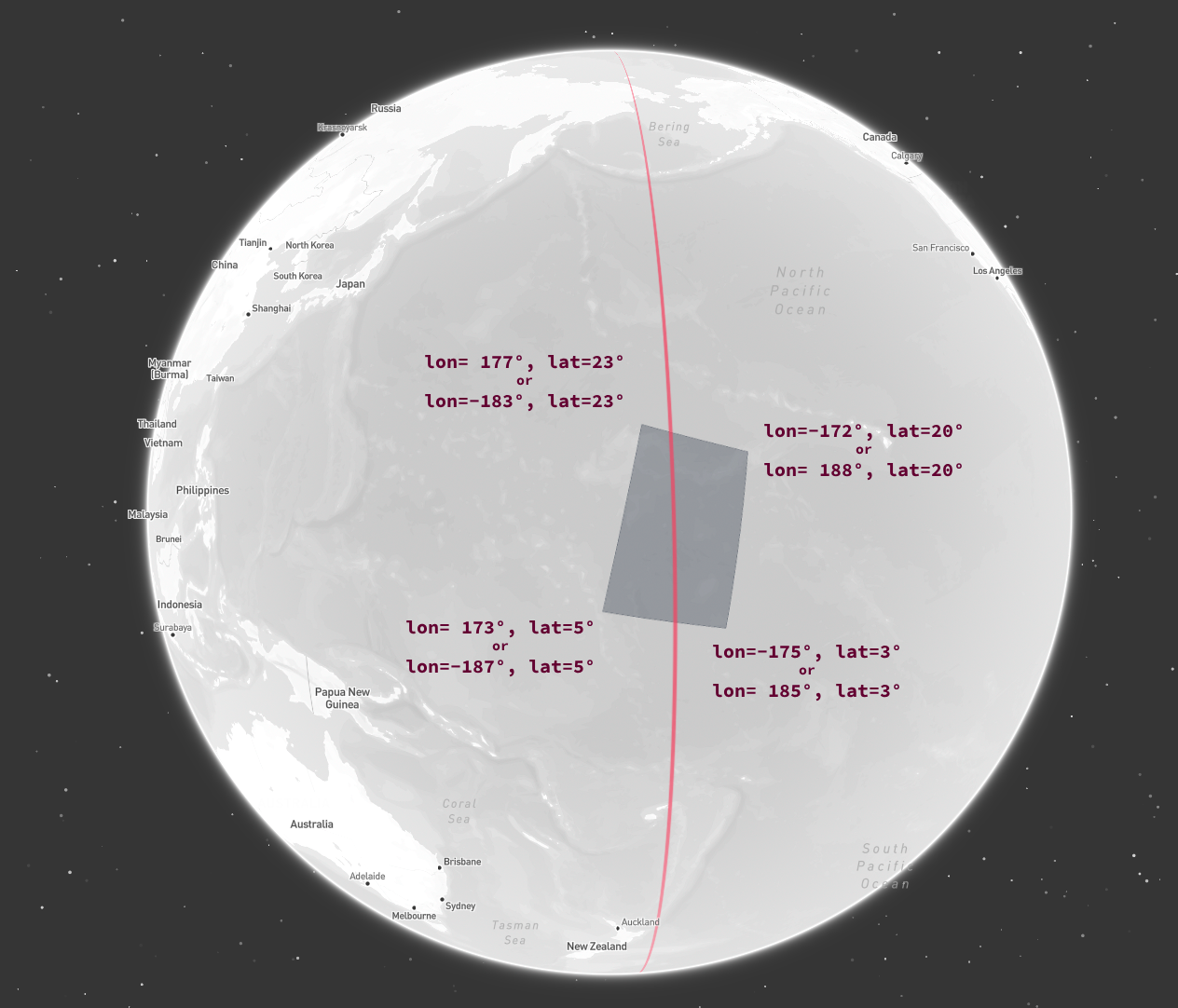

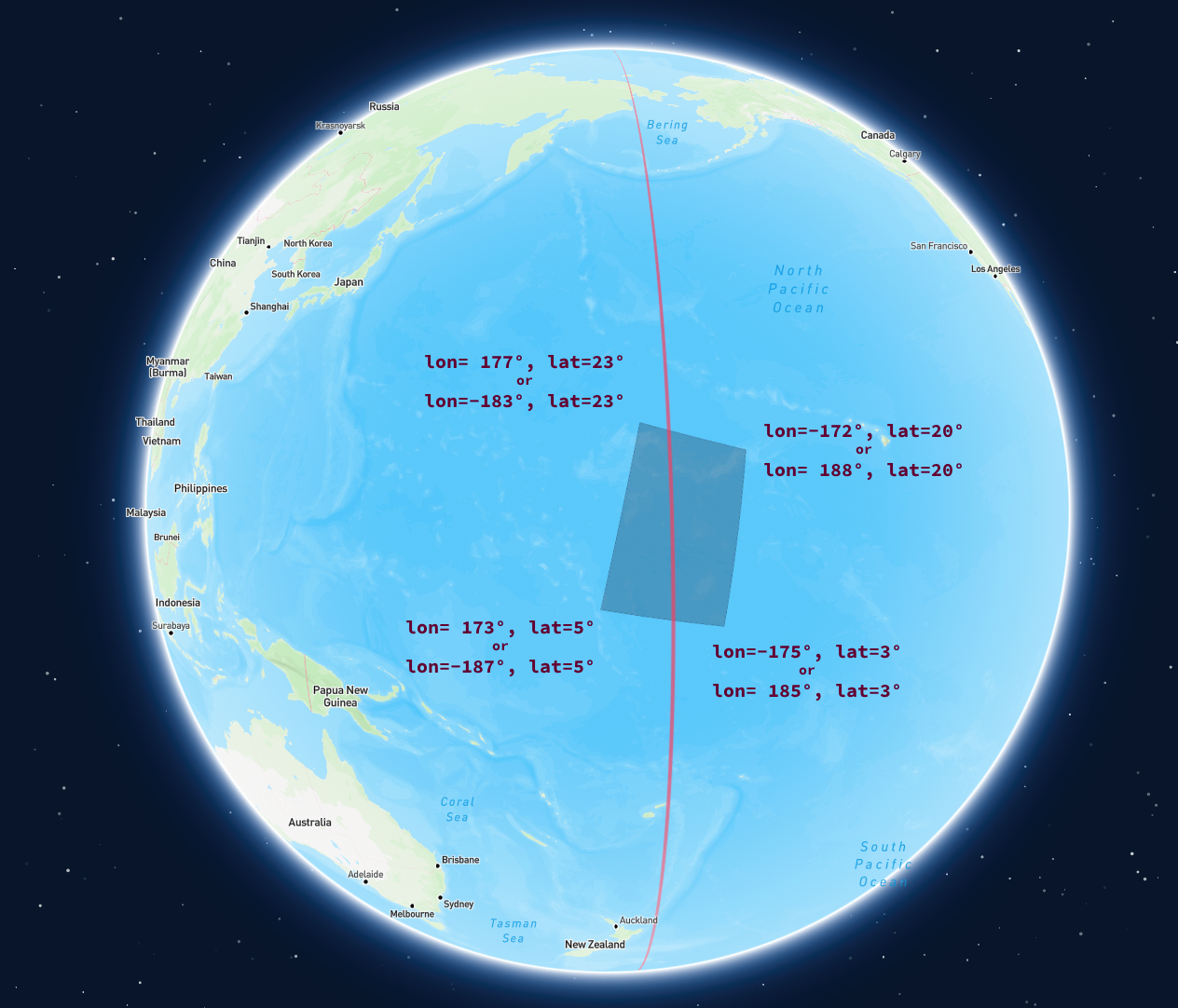

Geometries that cross the antimeridian are a common in satellite data, but can cause issues when not handled correctly. Take the followingPolygon that crosses the antimeridian.

Using exact longitude / latitude coordinates for each point

lon=173 to lon=-175 is interpreted as a 348-degree line crossing the null meridian, spanning nearly the entire globe.

Visualizations of such geometries often appear as shown below.

[-180, 180] bounds.

Expressing the geometry in such a way, may look like this.

Extending the longitude range beyond 180

-180.

Extending the longitude range below -180

Incorrect intersection check

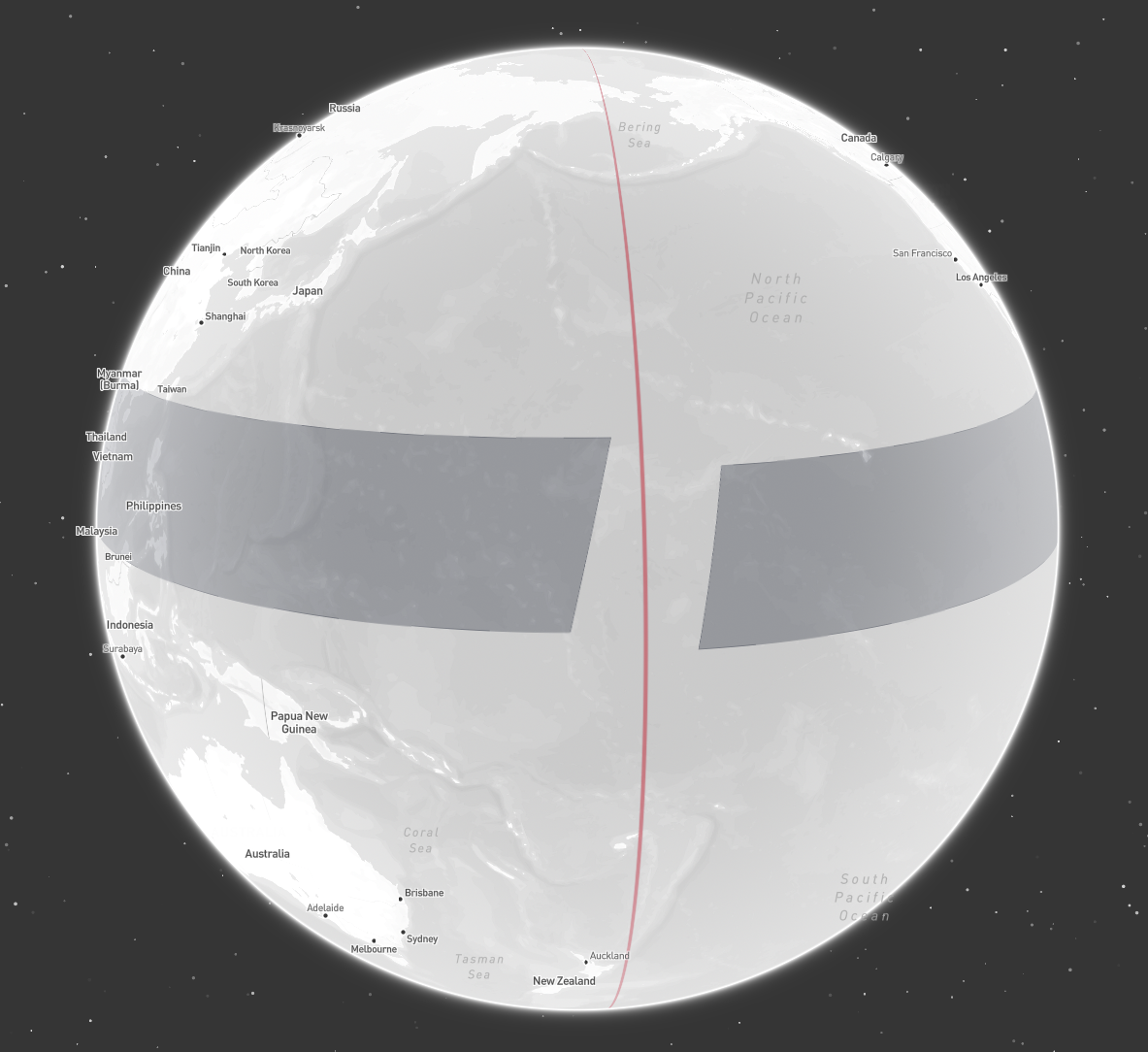

Antimeridian Cutting

Additionally, none of the representations shown are valid according to the GeoJSON specification. The GeoJSON specification does offers a solution for this problem, though, which is Antimeridian Cutting. It suggests always cutting lines and polygons that cross the antimeridian into two parts—one for the eastern hemisphere and one for the western hemisphere. To achieve this, check out the antimeridian python package, and an implementation of it in Go.Cutting the polygon along the antimeridian

- they conform to the GeoJSON specification

- there is no ambiguity about how to correctly interpret the geometry

- they are correctly handled by most visualization tools

- intersection and containment checks yield correct results no matter the coordinate reference system used

- all longitude values are within the valid

[-180, 180]range, making it easier to work with them

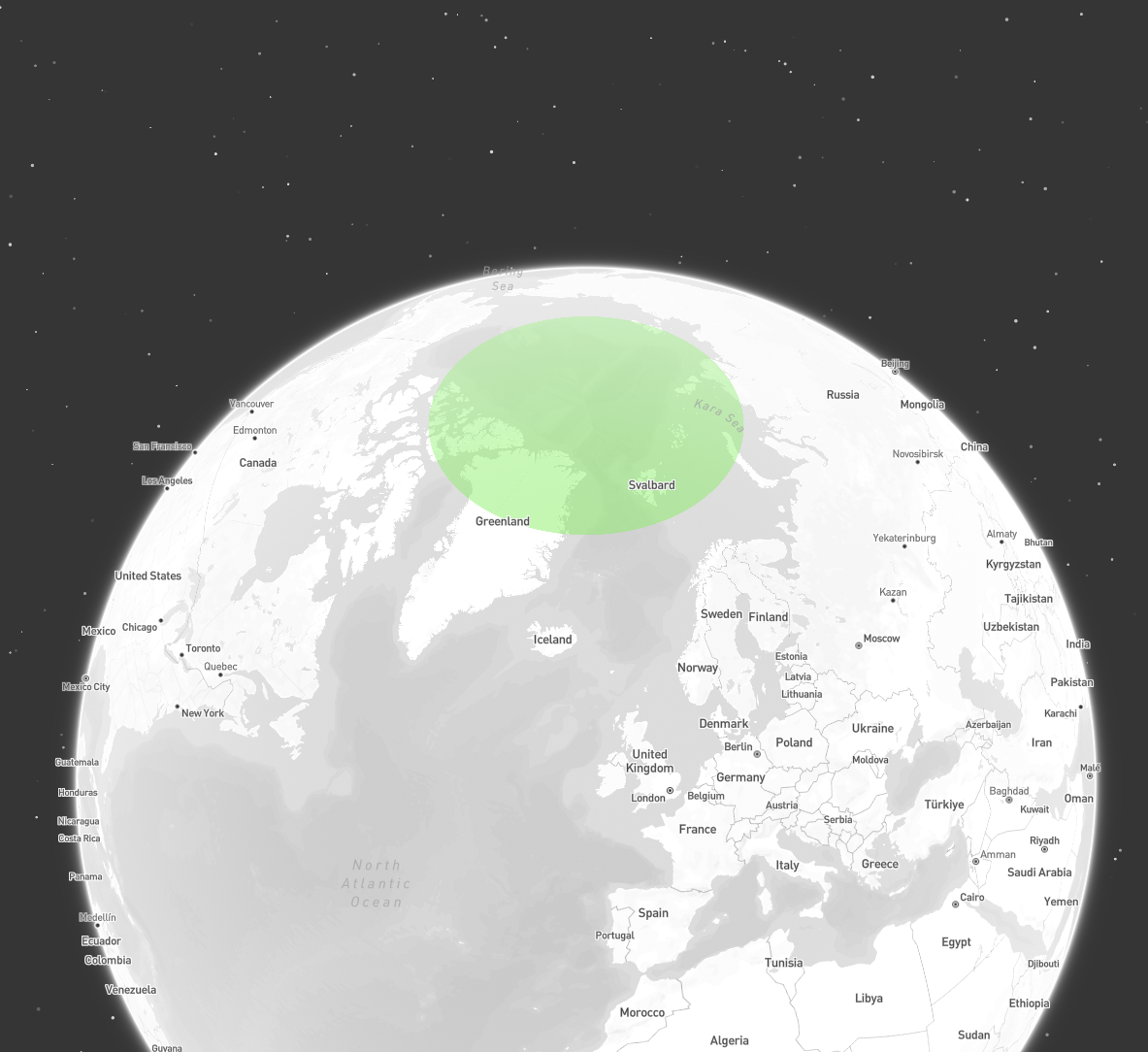

Pole Coverings

Geometries covering a pole can be particularly challenging to handle correctly. No single algorithm addresses all cases, and different libraries and tools may interpret them differently. Often, providing prior knowledge, such as confirming that a geometry is intended to cover a pole, can resolve these issues. For an example of this, check out the relevant section in the antimeridian documentation. Generally speaking though, there are two approaches that work well:Approach 1: Cutting out a hole

Define a geometry with an exterior ring that covers the whole globe. Then, cut out a hole by defining an interior ring of the area that not covered by the geometry.

Polygon covering both poles

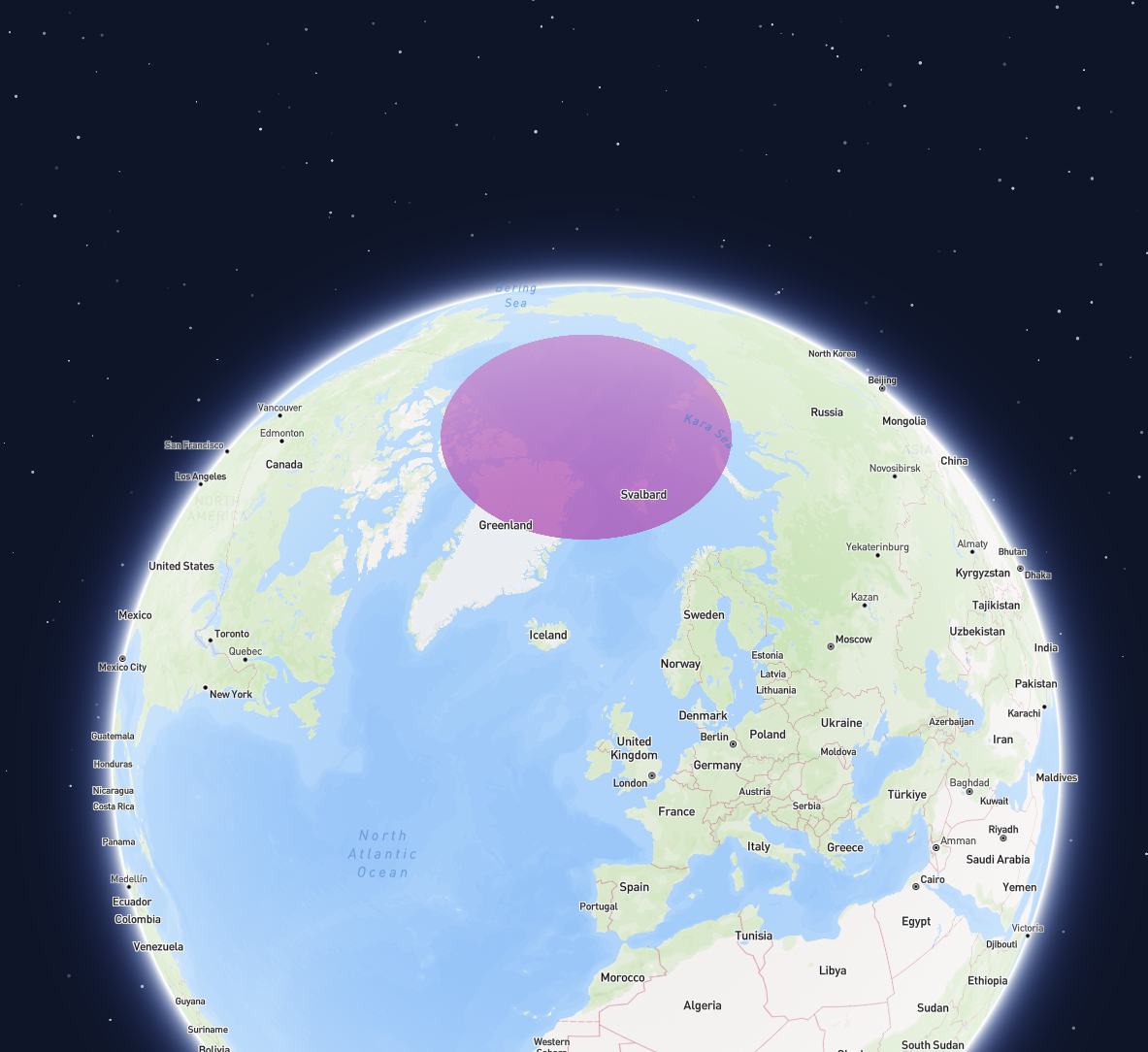

Approach 2: Splitting into multiple parts

Another approach, effective for circular caps covering a pole, involves cutting the geometry into multiple parts. Instead of splitting the geometry only at the antimeridian, also split it at the null meridian, and the90 and -90 meridians.

For a circular cap covering the north pole, this results in four triangular parts, which can be combined into a MultiPolygon. Visualization libraries and intersection/containment checks performed in cartesian coordinate space will typically handle such a geometry correctly.

Geometry of a circular cap covering the north pole